“Adult Children of Alien Beings” by Dennis Danvers is a science fiction novelette about the emotional journey of a man seeking the truth about his heritage and his parents, who were always rather . . . odd.

My parents weren’t like your parents, okay? The ones in the Mother’s Day cards and the Father’s Day cards. Who are those people?

My mother never drove. I never took lessons in anything. She told me as a child it was important to spend as much time alone as possible, preferably in the woods, maybe up in a tree or on a hilltop, while I was still open to the overwhelming mysteries of the universe. She didn’t start there; she worked up to it gradually. “Go outside and play” became increasingly ambitious and nuanced. The alternative was to be constantly underfoot. Mom needed her space before everyone said that. She started smoking because my older brother and I said it would make her look cool like the other younger mothers. Next day she bought a pack. She alternated between regular and menthol, pack a day.

My dad never had trouble showing emotion. He loved me like nobody’s business. I learned from observing him that at the end of sappy movies, if your face isn’t wet with tears, you haven’t been paying attention or you don’t have a heart. Not to have a heart was the worst. He asked me once if I wanted to learn how to fight, and I said no, and he said that was good because he didn’t know how. He was big and strong though he never worked out or did any exercise and ate anything he wanted. Mom was the same.

Dad loved to tell dirty stories. He did voices and everything. Mom loved to hear them. He made her laugh so hard, you could barely make out what she was saying: “Not . . . in front of the . . . k-k-kids . . . Bob!” Put that in a Father’s Day card: Thanks for all the smut. Knowing filthy jokes was every bit as useful as knowing how to fight, and Mom was definitely right about that treetop.

They taught me how to cook by smell. They both did it. The spice rack covered a wall, the spices in alphabetical order. They loved highly seasoned food. They never used recipes. You put your ingredients together, sniff out the spices for a dish, and cook. They didn’t believe in cookbooks, though I’ve dedicated the several I’ve written to them. They would find this amusing, laudable. The message I got from my folks loud and clear? The kid who’s just like his mom and dad? You have to wonder about that kid. You have to adapt, evolve, sniff out your own way in this world if you hope to prosper.

They’re both dead. They fell down an abyss while vacationing in New Mexico the year I graduated college. I only bring them up because at sixty-six, what I call semiretired, I’ve been digging into the family history, trying to unlock the secrets of my past like those celebrities on television. The thing is, Mom and Dad don’t have any. History. Now you see them, now you don’t. The entire family history narrated to my brother and me when we were little was a complete fabrication. They seem to pop into existence the year before my older brother was born. That’s when they started paying utility bills. They claimed to come from Colorado, but Colorado never heard of them.

I make the mistake of calling my brother with this information. He doesn’t see the big deal. Dad was always a bit of a storyteller. Maybe he didn’t get all the details right.

Their birth certificates are phonies, all their papers before my brother was born, even their marriage license. I had them examined by an expert. I’m back living in the house my brother and I grew up in, and all their stuff’s still up in the attic.

My brother moved away as soon as he thought I could handle things on my own, marrying and moving to his new wife’s town. He’s done that a few times since, different wives, different towns, while I’ve just moved all over town with different wives.

Mostly, the house has been rented out over the years. I didn’t want to sell it. I lost my last wife when it happened to be vacant, so I moved in. Lost, as in, she left. That was four years ago.

“What kind of expert?” my brother said. “Who believes experts?”

I gave up on my brother. I kept looking for our past.

Which led me to this guy, Dr. Deetermeyer, another expert. He’s looked over all my documents regarding my parents, as well as examined surviving articles of clothing belonging to them—my mother’s favorite scarf and one of my father’s cardigans—if you want to call snuffling them like a hound dog an examination. His office at the university is cave-like with six-inch pipes crisscrossing the ceiling, thick with yellow paint like lemon chiffon. The bookcases are crammed chaotically with books, papers, sandwiches, soda cans, videotapes, and tiny hand-painted soldiers from ancient armies. There’s a Rousseau print of some colorful craziness in the jungle and four or five framed degrees from prestigious universities. His first name is Simon. His middle name is Emmanuel. He’s at the end of a long, narrow, buzzing-fluorescent-lit basement hallway with no other doors. There’s nothing else but a bulletin board with band flyers from 2004 and numerous opportunities to study abroad. I almost didn’t knock. It smells like burnt coffee and rotten citrus and the faintest whiff of pot. The lone window is ancient frosted safety glass, tilted open a crack to reveal a hurried blur of student legs moving by, mostly bare. It’s a warm October day.

“Your parents were aliens,” he says. “Part of an exploratory expedition that arrived in the United States shortly after the outbreak of World War II and departed in 1969.”

“Aliens.”

“That’s right.”

“And that makes me and my brother?”

“Aliens.”

What to say to a totally tenured nutjob? I’m trying to remember who sent me to this guy. That weirdo at the Department of Historic Resources? Odd, to say the least. The past seems to do that to people. I should’ve left it alone.

“Ice cream,” Deetermeyer says.

“What about it?”

“They loved it, all year round.”

“So what? Lots of people love ice cream.” I start to rise. I have a hungry parking meter waiting. I gave my last quarter for this nonsense.

“Peppermint.”

That stops me. For my parents there was only one ice cream flavor, peppermint. Since it’s not readily available all year round, they stocked up every Christmas, loading a big box freezer full to overflowing in the basement. Dad, who did all the grocery shopping since Mom didn’t drive, sometimes took me along to help load up the cart. We both wore gloves for the occasion, like cartoon characters.

“With chocolate sauce,” Deetermeyer added with a little nerdy gotcha smile.

“How did you know that?”

“It’s an alien delicacy. They love peppermint and chocolate together. They love all the mints, but like peppermint the best. That’s what they found of greatest value here, mint and chocolate.”

“This is stupid. I’m human. I’ve been to doctors my whole life—my parents too. Somebody would’ve noticed if I was an alien.”

“Your form is human; your essence, alien.”

“What the fuck does that mean?”

“Your parents’ bodies were alien adaptations of the human form using human DNA. Certainly, to the medicine of the time, they would’ve seemed perfectly normal, as would their offspring, but they preserved and passed on their alien nature to you in a thousand subtle ways—their legacy. They reproduced at a somewhat higher rate than the general population. They were, after all, far from home and lonely. They were always deployed in male/female pairs. Clearly the pair bond is exceptionally strong among them.”

He seems absolutely serious. “Clearly. This, uh, alien essence you spoke of? How might that manifest itself in the, uh, offspring?” I try to keep a neutral expression. I notice that what I took to be ancient armor on the tiny soldiers might be their limbs and torsos; their weapons, household appliances from distant worlds.

He tilts his head back, aligning his trifocals to draw a bead on me. He’s used to skeptics. “Just you and your brother?”

“That’s right.”

“You’re the younger, I imagine, the Quester?”

My brother won’t even look for his car keys. “I guess you could say that.” I am the one who came down a narrow hallway to discover this loon, not exactly the quest I had in mind.

“Indeed. Gender and birth order are highly determinant in alien families. Stop me when I’m mistaken: You and your brother are four to five years apart, widely divergent in your views. You live in separate cities and prefer it that way. Presidents you hated; he loved—political polar opposites, you can’t seem to agree on anything. You share some telltale traits, however. You’re both inordinately fond of animals—dogs, cats, birds, any animal really. Alien males almost never hunt, though the elder is likely to own several guns. You’re both cynical about most things, but sentimental in love. You’re typically serial monogamists. Your wives—”

I hold up my hand. “Enough. So you want to tell me why aliens came here and what I should do about it?”

“As for why, you’ll have to wait for the aliens to return. There’s no shortage of competing theories to occupy you in the meantime.” He smiles like this prospect is supposed to cheer me up. “To help you deal with this startling discovery you’ve made about yourself, there is a support group, ACAB, that does lots of fine work. Much, if not all my research, is based on in-depth interviews with its members. Perhaps, when you’re ready, we might conduct such an interview.” He sifts through the detritus on his desk to unearth a slender pamphlet. Adult Children of Alien Beings. He staples his card to it, like he’s handing out an assignment.

I snatch it from his hand and flee his office, but he leans out his office door and calls after me, “Email me with any questions. Stop by anytime!”

I sprint up the narrow stairs into the street. I examine the card. His name and information, the university logo. The Department of Secret History. There’s a sign by the basement stairwell that reads the same, looks like all the other signs up and down the street. I had no idea the university had such a department. Makes sense, I suppose, that I wouldn’t. These houses used to be the mansions of the idle rich. They’ve seen their share of séances and crackpot rituals. That their basements now house such mysteries seems appropriate somehow. Who else has time for them but the rich and universities?

I don’t have time to ponder this further because the meter cop is about to write me a ticket even though I’m right here, keys in hand, and we both watch the time run out together. It takes forever to talk him out of it. He makes a big deal, like world justice depends on me paying for my parking crimes. Several cars pass, coveting the spot while we bicker. He manages to be a total asshole before he finally relents. I get into my car, rattled from both encounters, loon and asshole. Sometimes I just don’t understand people!

As the thought flits through my brain, I freeze, frozen in the process of shifting into Reverse.

Sometimes I just don’t understand people.

I drop back into Park. Dad said that all the time. I can hear him saying it. It was like the chorus of my childhood. Like he really meant it, felt it deeply. And Mom would put her arm around his shoulders and murmur, “It’s all right dear. Everything will be fine. You’ll see. It will all work out.” And he would look at her like she was the only one on the planet who truly understood him.

Maybe she was.

I touch the brochure in my pocket, next to my heart. I owe it to them to check it out. I’m the Quester, after all. Nobody else is going to do it. I started this searching-out-my-roots business in the first place to find out where I came from. From another planet makes as much sense as from nowhere.

Someone honks his horn at the old man frozen in his clunker at the parking meter, his turn signal on like he’s going somewhere, but too addled apparently to give it the gas. I understand the honker’s feelings completely. I drop it into Drive and gun it.

I know what he’ll say, but I have to talk to my brother about this. Everything Deetermeyer said was true about us and more besides, but this isn’t like the Bushes or the wars or same-sex marriage or the NRA or roundabouts or Obamacare or NASCAR or climate change or the Dallas Fucking Cowboys. This is more like Animal Rescue.

Alien Rescue. Ourselves. That’s the key. To accept who you are so you can move on in a meaningful way. Now that I’ve read the brochure, been to the website, and pondered the evidence at length, it makes more and more sense.

In fact, it makes sense of everything.

One story of dozens I could tell: When I was nine or ten, Mom did a Paint by Number of a mountain landscape, systematically switching all the paints. She had a list of all the numbers and their substitutes taped on the wall where she worked on it meticulously for hours. She was quite pleased with it and just sat smiling at the scene while it dried, smoking a cigarette. How about? This was a menthol day, Alpine or Newport, one of those. The sky was the color of the pack. All the colors were wrong. Under the deep turquoise sky, the snow was way too blue. The evergreens were brick red.

Dad traveled. District sales manager. He hadn’t been around for the weird Paint by Number project. My brother ignored it, of course, like he ignored everything else that wasn’t about him. I was there for the unveiling, when Mom showed Dad this goofy Paint by Number, and they both had a drink and a smoke and sat there smiling at it teary-eyed, holding hands. They hung it up in their bedroom and locked the door for a while.

My folks were noisy lovers. It was many years before I realized not everybody grew up listening to their parents fuck, trying to picture it, what would make them groan and thump in that distinctive rhythm. She would scream his name in a way that I knew meant, despite its volume and intensity, that she wasn’t mad at him but the opposite, a mystery I pondered long into the night.

Turns out Paint by Number was wildly popular among the aliens, and that a code circulated among them to translate certain landscapes—specially designed by an alien who had infiltrated the design department—into the palette and contours of their home world. There’s an image on the ACAB website of the scene my mother did that looks exactly like the one I remember. That’s what was going on with Mom and Dad: They were remembering home, when they met perhaps, and fucked like crazy, like they were young and in their old bodies again. If you examine it closely, supposedly, the elk in the middle distance has three eyes. The JPEG is too tiny to tell. Unfortunately, Mom’s painting hasn’t survived. She had a big yard sale the spring before they fell into the abyss and practically gave away all her artwork.

I explain all this and more to my brother over the phone. We both hate talking on the phone, but we live five hundred miles apart. Face to face is reserved for dead, dying, or getting married again. We’re both between. The last time we spoke was a couple of months ago when he called to tell me he was moving out and to give me his new address. That’s when I told him about my early research, before Deetermeyer. Probably not the best timing.

It takes him a while to just shut up and listen, so I really lay it on when I finally get an opening, maybe give him a little too much to process all at once.

“Aliens,” he says. “Stan, I think you need help, professional help.”

“Dr. Deetermeyer is a professional, Ollie.”

I can feel the phone grow cold in my hand. “I told you not to call me that,” he says in his gruff Clint Eastwood voice. He thinks it’s intimidating. It just makes him sound old.

“It’s your name. It’s what Mom and Dad always called you. It’s what I called you until you got a pole up your ass about it. I can’t remember. Was it Kristi or June who put the idea in your head there was something wrong with it? It’s on your birth certificate, Ollie, the first real document in our parents’ lives on Earth!”

“Our parents named us after a couple of buffoons, Stan!”

“They didn’t know any better. They were aliens! Don’t you see? They loved Laurel and Hardy, so why not name their sons after them? It’s so typical for the elder son of aliens to resent their peculiarities and crystalize his rage in some trivial wrong like a naming that merely expresses the parents’ true alien nature. They knew how to laugh, Ollie. Something you could stand to work on. Compassion. Understanding.” Aliens love slapstick too, but I don’t go into all that. Ollie’s at war with that side of his nature.

There’s a long silence. I know my brother. He’s struggling with his better self. He wants to tell me to fuck off and hang up, but he wants to rise above it and be the only rational member of his crazy family. You’d think after all these years he’d give that one up. He’s just not that good at it. “I prefer Oliver,” he says icily.

Oh please. This is typical firstborn alien brother behavior, to feel betrayed rather than blessed by his alien heritage. They invest minutiae, such as a mere name on a birth certificate, with great significance. They’re into vows, lines in the sand, all the rest of it. They have no control, the victims of their own symbolism. It’s like waving a red flag in front of a bull. I’ll demonstrate: “Ollie, Ollie, Ollie.”

He hangs up. It’s just as well. There’s no way I can convince him Mom and Dad were aliens without further proof. I email him all my evidence, direct him to the ACAB website. Maybe he’ll read it, and maybe he won’t, but most likely he’s absolutely certain I’m just crazy. Nothing new under that sun.

As you might imagine, paranoia runs high in the ACAB community, so there’s not a lot of face to face, but some of us aren’t so comfy with the online thing either. Am I really chatting with a fellow ACAB member in Santa Monica, or is it some FBI guy in Quantico taking a little time off from pretending to be a thirteen-year-old girl entrapping sleazeballs to infiltrate a fringe group for a change of weirdness? How’s that for a career choice? And I’m the crazy one? Anyway, the local ACAB group’s fairly tiny. We meet at the dog park second and fourth Tuesdays at dawn. (Fifth Tuesdays, we take the dogs to the river in all weather). We’re all early risers, and so are our dogs. We have the place mostly to ourselves. We watch the dogs play while we discuss alien issues, sitting in a row on top of one of the long picnic tables, our feet on the bench. Summer mornings, we’ve had as many as seven or eight, winter months it’s usually just the four diehards.

Today it’s Katyana and Bill and me. She’s in the middle, I’m on her right, and Bill’s on her left. Dave is on his fourth honeymoon. Most of the regulars are my age, fifties, sixties, born from the late nineteen-forties into the sixties. Katyana’s thirty maybe. She mentions her ex now and then but never gives out any details.

She believes the aliens didn’t all vanish one way or another within a month of each other like my parents did, but that some hung around longer, maybe even more showed up. She’s proof, she says. Her next older sister’s nineteen years older. Her parents were old. Katyana’s intense, and so is her blue-gray standard poodle Avatar, so no one argues with her. Opinion’s sharply divided in the ACAB community on the Departure Issue, but she’s definitely in the far fringe minority. I don’t like to get into that controversy. I’ve got enough to figure out in the mainstream fringe.

I tell them about trying to get through to my brother. “I don’t want to give up on him.”

“Let it go,” Bill says, what Bill always says. He used to be a Unitarian minister. He gave a few too many sermons on aliens. Unitarians aren’t as open-minded as they like to think they are. Now he has a pug named Clyde. “There’s no convincing some. It’s for a reason your brother is the way he is. It’s all part of the plan.” You have to watch Bill. He’ll get to talking about Shinto gateways and fail to notice Clyde’s adding a lovely dump to the scene. On this issue he may be right, however.

To maximize dispersal of alien seed, the predominant theory goes, ACAB brothers don’t get along, move apart, and take multiple partners in order to create a far-flung network of alien descendants in every walk of life to greet them when they return. Ollie’s pig-headedness, Bill’s saying, serves a genuine purpose, but I’m not entirely convinced. How is willful ignorance of one’s true nature better than self-knowledge? What good will Ollie be when the aliens return, if he doesn’t even know who he is? I sort of nipped the alien plan in the bud when I got a vasectomy after my second wife had to quit taking the pill because of terrible migraines. No regrets. No children except some wonderful steps. I don’t think they figure in the alien design, though I might’ve brainwashed them in some way. I’ll have to ask them next time I see them. I have them over for dinner a couple of times a month. They’ve developed alien palates. Like many ACAB’s kids of multi-married parents, they’ve shown a reluctance to marry themselves.

Katyana shakes her head at Bill’s advice as he elaborates. How you elaborate on let it go, I don’t know. I’m not really listening. I’m not so much looking past Katyana at Bill, but at her lovely profile as she rejects Bill’s wisdom, using his pious tedium as a pretense to admire her beauty. I have to look away.

Out in the barren wasteland of the dog park, my dog Myrna, usually a clever border collie, is desperately making a fool of herself to catch Avatar’s attention—crouch, spring, whirl, dash—but he’s having none of it, making his stately progress around the perimeter, pissing. He makes it look like a yoga pose. She does not exist to him. If she’s not careful, he’s going to piss on her head. I can’t watch.

“You should devote your energies to finding one of the old aliens who stayed behind,” Katyana says to me. “They’ll know whatever you wish to know. You shouldn’t care so much what your foolish brother thinks.”

She gives me a mildly scolding look, and I’m unnerved at how much I wish to please her. Forget my brother? Not a problem. Dave’s of the opinion, he confided before he left for Cancun, that Katyana’s not ACAB at all, just crazy. I like her, though, and she does look like an alien, has all the telltale features. A beautiful alien. I like having a plan. Let it go doesn’t feel like a plan. “How do you think I should go about finding an old alien still hanging around Planet Earth?”

Bill heaves a gentle ministerial sigh at my foolishness. Screw him. I interrupt his judgment to point out Clyde’s taking a crap—part of the plan no doubt—and Bill trots off to tend to it. Katyana smiles, cocks an eyebrow. It’s just the two of us. She has enormous eyes even for an ACAB, whose eyes tend to run large. “Think like one of them. That shouldn’t be so hard for you. You’re the most alien of us all. Who knows more?”

It’s true. I’ve sort of thrown myself into it, like an abyss, researching the subject endlessly, contributing regularly to the ACAB blog. I don’t know whether she’s teasing me or has faith in me, but Katyana inspires me to ponder the issue like worrying a bone. If any of the original aliens are still among us, how would I go about finding them? They all supposedly died somewhat mysteriously within a few months of each other, leaving no bodies behind, which is generally held to mean they abandoned their human form, their mission fulfilled, and left the planet en masse, by wormhole or starship. Opinion is divided and not really relevant to the more important question—did any remain behind? Even the most ardent believers in the Stayed Behinds or the Left Behinds, depending on who you ask, admit only a handful would be living now. It would be like finding a needle in a haystack, like aliens finding Earth on the outskirts of the Milky Way. If you’re an ACAB, you have to believe anything is possible.

Later on, I’m sitting at home watching a rehash of the Black Friday craziness on TV with Myrna’s head in my lap, muttering, “Sometimes I just don’t understand people,” as they run clips of folks trampling each other for deals to show how well things are going this holiday season, when it hits me: Christmastime. Peace on Earth. “Away in a Manger.” Hysterical consumerism and lots of sappy movies—the season for aliens to restock their freezers with peppermint ice cream and cry happy tears. I love Christmas. I’m not a believer, but I love the story—strangers in a strange land, the most important kid on the planet born in a barn. Come let us adore him. Nothing wrong with that.

It’s not hard to figure out where I might spot a shopping alien early in the holiday season. The peppermint ice cream at the Kroger fills an end box across from the soft cheeses where I figure I can dither indefinitely over whether to get dill or pimiento or chipotle or just forego this artery-clogging glop altogether—one of the privileges of old age, indecision—while I wait for an old alien. It’s senior discount day. The aisles teem with us. Still, for even so weighty a question as to brie or not to brie, there must be a limit, and fairly soon I’m joined by the youthful dimwit I recognize to be the manager, who pretends to tidy up some tiny cheeses with smiling cows on the label. There are cameras everywhere. Alert: Senior beached at the cheeses without a purchase for going on a quarter hour.

“Are you finding everything all right, sir?”

Who can honestly answer yes to that one? Sir with the right inflection means doddering old fool in managerspeak. Screw you very much, Sonny Boy, I’m waiting for ancient aliens. “Just fine,” I say. He glances down into my basket. There’s a bag of frozen kale thawing, a pound of black beans, and a couple of yams to show I’m serious about the shopping thing. Aliens didn’t eat cheese and ice cream and thick, juicy steaks because it was good for them. They knew they were only in their human form for the short term and didn’t have to live with the consequences. I’ve been vegan since my heart attack four years ago this spring. I’ll have to move along. There’s nothing within arm’s reach I can eat. Maybe I can lurk by the frozen berries and dither there if the sight line’s right. So far there’s only been a handful of single quart peppermint ice cream buyers. Nobody’s made a purchase of alien proportions. Dad and I used to empty the case as soon as it showed up. If the store runs out early in the season, Dad explained, they restock, and you can hit the same store twice in one year. If you wait around till there’s no Christmastime left, they might not bother. Some years we had to hit multiple stores. This is probably the peppermint cusp.

“Were you looking for a mild cheese?” the manager ventures. “Or something sharper?”

Than you? I point to the label on the cheeses he’s fussing over. “Those cows there—are they organic? Where are they from exactly? They look so happy.”

“Hey Stan!” a familiar voice behind us says, and we both turn. It’s Katyana.

She’s a small, slender woman who lives alone, and yet her full-size shopping cart is filled to overflowing with peppermint ice cream, the case behind her, empty. My back was only turned for a moment. She’s quick. She could’ve easily slipped away unnoticed. “Katyana,” I say. “Fancy meeting you here.”

The manager seems surprised I even know someone like Katyana. Her arms are covered with tattoos, and her nose is pierced. She’s wearing what looks like one large tie-dyed scoop neck sock, boots, and a flannel shirt tied around her waist. Her earrings remind me of trout flies. The manager seems slightly terrified of her himself. She and I watch him retreat. I’ve never felt more alien. I like it.

“I’ve been thinking about what you said about finding an old alien,” I say. “I’m on a peppermint ice cream stakeout, and it looks like you just bought it all.”

She gives me this penetrating look, really drills in. The Christmas carols fade into silence, the fluorescents seem to dim. I can feel the cold radiating from her shopping cart. I’m slightly terrified of her myself. “I guess your wait is over then, isn’t it?”

“You getting some chocolate sauce to go with that?” I ask with a chuckle, though it comes out more like a squeak and a snort.

“I have plenty at home. Want to come on over for a bowl? I could use some help unloading this. Bring Myrna. She and Avatar can play.”

I’m a bad person. My dog’s out in the car. I know you’re not supposed to leave them unattended, even in December, but she loves it. Like most border collies, she loves to watch. I always park somewhere she’ll have maximum visibility to keep tabs on the flock. Katyana must’ve seen her when she drove up in her decrepit mini pickup. She had to know I was here.

I know what I just said about the health risks involved in the consumption of high-fat, high-sugar dairy products, but this is a unique situation. I’m intrigued. There is a far fringe opinion in the ACAB community that the aliens didn’t die, didn’t go anywhere, that they traded in their old worn-out bodies for new ones, that they traded in their old lives by necessity when they did so, in order to live new lives in younger, healthier bodies. Like Katyana’s. Old souls in young flesh. I’ve never liked this theory much because it would mean my parents didn’t die or return home from an important mission; they abandoned me and Ollie so they could live a new life without us.

Katyana’s saying it’s true. “Think of them,” she says. “You and your brother were moving on. Maybe they had health problems. A new life is a pretty wonderful thing.”

She says this like she knows what she’s talking about. We’re standing in the kitchen of her garage apartment. It’s dusk. The days are short. She’s backlit by the light through the kitchen door. A light over the stove shines on her face. I try to imagine it, a new life.

She puts on a kettle for tea. On the wall beside the stove is a huge spice rack like the one I have at home. I know now why Deetermeyer snuffled my parents’ clothes. He was looking for this scent. If I were to bury my nose in the flannel shirt Katyana is wearing it would smell like this spicy, steamy kitchen. She says she will miss this place, a cozy garage apartment behind an empty house with a Sold sign in front. The new owners want her out by the end of the month, so their son can move in. Happy New Year.

She dishes up huge bowls of peppermint ice cream and explains that aliens have mastered the human genome, and periodically they trade in old bodies for new ones—all of them. Katyana’s terribly sorry, but she’s lied to me, she says, out of necessity. She isn’t the daughter of original aliens. She’s one of them in a new body she’s only had for slightly more than a decade. “Y2K was a busy time. All the hubbub made it easy to launch a new life.” She apologizes for the deception, but she had to decide if I could be trusted with this knowledge. If I was truly ready. She has a tiny urn filled with chocolate sauce imported from Switzerland with a little spigot. She loads it on. My mouth is watering.

I follow her into the tiny living room, and we sit down. I’m not surprised to see, hanging on the wall, a Paint by Number identical to my mom’s. I still can’t make out that third eye.

“Ready?” I ask.

“For a new life, a new body.”

At this point Myrna is cowering under the coffee table, taking a break from Avatar who, although he’s neutered like all alien dogs, kept humping her when we first got here, head, rear, anywhere, while Katyana and I were loading the freezer in the garage with ice cream. Avatar seems to have trouble finding a happy medium. Katyana told him to quit, and he did, but Myrna doesn’t trust the situation and would like to leave now. I’m all ears, however, and I ignore her beseeching looks.

“Will your car make it to New Mexico?” Katyana asks, her mouth full of ice cream. She doesn’t have to tell me her truck won’t. The inspection sticker expired in March. You can hear and smell that the exhaust system won’t pass, and there’s a huge crack in the windshield. I wouldn’t drive it anywhere I couldn’t walk away from.

“I think so,” I say, though I’m not thinking. My mouth is frozen in creamy fat sweetness, burning with peppermint and dark, earthy chocolate. It’s like crack but more deadly. I swallow it anyway. She doesn’t have to say where in New Mexico. Mom and Dad’s last destination.

We’re headed for the abyss.

We talk for hours working out the details. I have a thousand questions. She has a thousand answers. I cook, we eat. I can’t remember the last time I was so happy. It’s not the prospect of a new body, though that would certainly be welcome, if still difficult to believe in. It’s just a night like this, full of questions and answers, plans for an insane odyssey, a midnight meal. It’s been a long time. It’s nights like this you live for, isn’t it? Nights you never forget.

You must admit I have to tell my brother about this, and he has to listen. He’s older than me, for Christ’s sake. He could go any time. He has a terrible diet. I call him from the gas station where they’re making my Saturn roadworthy. It only has to make it one way, I explain to the mechanic, though I don’t explain why. Katyana and I plan to leave first thing in the morning. It’s a terrible time of year to travel, but what can you do?

Ollie doesn’t pick up right away, probably still pissed from the last time we spoke.

When I tell him where I’m going, he shuts up in a hurry. “It’s not an abyss,” I explain. “It’s a transdimensional portal to the nearest alien medical facility where the procedure will be performed. Because of the transdimensional drift, when I return, I’ll actually emerge back here in town.”

I can hear him breathing in and out. Finally he says, “What does she look like, Stan? This woman half your age you’re driving across the country with in an old clunker?”

“Like an alien goddess.”

“Stan, you can’t do this.”

This time I hang up on him. The elder alien brother telling the younger he can’t do something is a near guarantee it will be done. That’s how I ended up married the first and fourth times. I couldn’t let him tell me what to do. Not that this is about another marriage. I was just trying to offer him the opportunity for a new life as well, not another chance to get all up in my business, like he knows a thing about wise romantic choices.

Katyana has a friend we can stay with in New Mexico while we’re scouting out the abyss, so we’ll be cool once we get there, she says. We just have to make it from here to there. Money’s tight for us both, her more than me. Social Security keeps me afloat; I do a little freelance, some teaching. I used to write all kind of things before the cookbooks clicked. The web killed cookbooks. Recipes are free, as they should be. I never believed in recipes anyway.

Her unemployment just ran out. She was an archeologist working for the Department of Transportation. You can imagine how that went. She, of course, has no parents she can turn to. They’re light years away. Gas will cost plenty, meals. At first, she’s talking like we should just drive straight through, just go for it, four hour shifts, but over dinner in Knoxville, she asks, “How many more hours?” She looks totally beat, and she’s supposed to take the wheel after dessert.

There’s a table topper for Seasonal Treats, and Katyana ordered two peppermint ice creams with chocolate sauce for dessert even before she decided on dinner, which drew a bemused look from the waitress, a lanky, curious blonde. Katyana told her that we’re going home for the holidays; that no, she doesn’t know what kind of feathers those are on her earrings; that yes, people have told her she looks like some actress I’ve never heard of who “kicked butt” in a movie I have heard of but assumed I wouldn’t like. I suspect the waitress is smitten. Perfectly understandable.

I break the news. “We have to cross Tennessee, Arkansas, Oklahoma, a bit of Texas, and half of New Mexico, and we’re there. Twenty-one or -two hours if we don’t stop too often, though we need to give the dogs a proper walk sometime, or they’ll drive us crazy.”

We got a late start. It took a little doing getting Avatar and Myrna installed in the backseat where they seem to have worked it out. Our stuff is crammed in the trunk. The abundant caffeine Katyana’s downed in a myriad of forms is starting to fade, and she’s about to crash. She revives a bit when the ice cream arrives. She digs in for a while. I pick at mine. One binge is enough for me. The sweetness is cloying, the fat, toxic. I let it melt.

“How come you never hit on me?” she asks, seemingly changing the subject. She’s finished her bowl and accepts mine, stirs it into a dark purple swirl I remember from childhood. She sucks on the spoon with each bite.

“I’m twice your age,” I say.

She shrugs a shoulder, takes another bite. “That doesn’t stop Dave. That doesn’t stop Bill.”

“Bill? I didn’t know he had it in him.”

“Oh yeah. He started talking tantric with me one morning early when it was just the two of us, if you can imagine. But back to you. I’ve seen how you look at me. Are you a perfect gentleman? I’ve heard of those.”

She’s teasing, flirting a little, but I know what she’s asking. “Have you read The Sun Also Rises?” I ask.

“That’s Hemingway, isn’t it? I read the other one. A Farewell to Arms. Why?”

“I was looking for a delicate shorthand. You’ve heard of prostate cancer? I had surgery five years ago. They warn you that there are risks, but the percentages look terrific, and if there are any problems, they tell you, we have these great drugs now. I know you’ve heard of Viagra. Didn’t work, horrible side effects. I’ve been a perfect gentleman ever since. Just recently they released a study saying surgery like mine wasn’t maybe such a great idea after all.”

I’ve never made this speech to another person on Planet Earth before.

She holds my gaze. She takes my hands. “I’m sorry that happened to you.”

I shrug. “The cancer’s gone.”

“Whenever you’re ready,” the waitress says, laying down the check, giving Katyana a dazzling smile. Surely, she must be thinking, this old man is her father. Little does she know we’re only passing through on our way to another dimension where Katyana’s nearly twice my age.

Out in the parking lot, Katyana gives me a daughterly hug, and we get in the car, me behind the wheel. Before I put the key in the ignition, she asks, “Can we afford a night there?” pointing to a Quality Inn a few parking lots over. “They usually take dogs.” We means me. She’s totally broke, her last credit card in tiny pieces. She made her fingers little scissors when she told the tale last night.

When they hear the word dogs, they come wide awake. Avatar’s long and curly snout thrusts forward, Myrna beside him, peering out the windshield, like they’re reading the marquee: Welcome Chris and Kristin. Can’t disappoint the flock.

“No problem,” I say, feeling a little more like “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place” than The Sun Also Rises. Everyone should read Hemingway for a dose of lean despair when the AARP card comes in the mail. The Old Man and the Sea, however, is just exhausting. I’ve never been much of a fisherman.

All they have in a dogs-allowed room is a king-size bed. After we feed and walk the dogs, who’ve bonded and feel refreshed, they break into a crazed play session chasing each other all over the tiny room while Katyana and I cower and laugh on the bed. Avatar rolls over on his back and lets Myrna climb gleefully all over him. Her breath heaving, her tongue lolling, Myrna smiles at me in delirious gratitude for this Great Adventure, and she’s sorry she ever doubted me.

Make no mistake. If I were not an impotent old man, I’d throw myself at Katyana’s feet, on top of her, into the abyss—whatever would serve to woo her, but that’s not how the world works, is it? Not this one anyway. But it’s okay. It really is. It makes things so much simpler in a way.

I lie awake and listen to her sleep, what I can hear over the dogs’ companionable snores. They’re piled together between us. I listen to her dreaming—troubled murmurs, then something like a whimper and silence.

When I finally fall asleep, I dream I’m living a new life. I step out of a shower into a steam-filled motel bathroom and wipe the condensation off the mirror so I can see the new me. I look exactly the same. The scar runs from an inch above my cock to a couple of inches below my navel.

In the morning, Katyana’s sick, and she says not to let her order any more ice cream, and she dines on mostly salads and toast all the way to New Mexico. There’s lots of time. The radio’s broken. We talk across four states as we watch them glide by. I tell her how it was my third wife, the engineer, who came up with the system I use to produce accurate recipes from a chaotic intuitive process by weighing all the ingredients before and after, so I don’t have to keep track along the way. I tell her how I fell so hard for my second wife I went crazy, crazier still when we split up ten years later.

She tells me when she was twenty-two, the age she was when she was renewed, as she calls it, she was terrified to live a new life, had hung on to her old one for way too long and was afraid of being young again—she’d made so many mistakes the first time. She didn’t step outside for two weeks, and only then because she’d run out of food.

“Why didn’t you just call for delivery?”

She laughs. “I was more scared of who might show up, the face to face. Like they might spot me right away, you know?” She does a gruff voice: “You’re alien, aren’t you?” She laughs again. “Got over it though, as you can see. I was going to get it right this time, not make the same mistakes.” She looks out at the desert landscape, and the smile quickly fades, and her eyes are sad and creased with worry. We’re close. The closer we get, the more worried she becomes. We just left Texas.

“Tell me about your friend. Jack, isn’t it?”

“That’s right. He’s just a guy.”

“Nice of him to let us stay with him. He knows we’re coming, right?”

She doesn’t answer right away. “Sort of. He sort of knows I’m coming. I—I didn’t tell him about you exactly. I’m sure it will be okay.”

I look in the rearview at Myrna and Avatar leaning up against each other like mismatched bookends, listening to our conversation. ACAB dogs are fluent in their owners’ languages and often communicate telepathically when the need is great. Myrna lays her head on Avatar’s heart and assures me everything will be all right. This abyss plan is my best yet, even better than moving back into Mom and Dad’s house, rooting around in my roots. Look how great that’s worked out. I adopted her from a shelter after the prostate surgery, when I was healed enough to stand a young dog straining on her lead. We’ve been through a lot together. I trust her judgment completely.

Katyana looks back from the desert. “Jack’s not alien, okay? He doesn’t know about us. We can’t talk about any of that crazy shit around him, is that clear?” She hears herself and shakes her head. “Sorry. I’m being a bitch. I just don’t know how he’ll react. I’m sure it will be all right.”

That’s twice she’s sure, so I get the picture. She hasn’t a clue, with the stakes a lot higher than taking some foolish old man to the abyss, and she’s scared shitless. I’ve been there plenty of times, but not today for some reason. I’m perfectly happy to be here. You may be like my brother and think I don’t know how crazy this is. Don’t worry. I do.

She tells me the story of Jack. He’s a musician who travels a lot, so he’s not here that much, but he likes to be home for the holidays. The travel gets too crazy then. He got stuck in a blizzard once for three days. Jack, she confesses, is her ex.

“You don’t seem surprised,” she says.

“I figure if you’re going to drive across the country to see a guy, it must be somebody like that. When did you see him last?”

“October. He played a gig in Charlottesville. He called me.”

I hope she didn’t drive that fucking truck of hers to Charlottesville, but I don’t ask. “So does he know you’re pregnant?”

It takes a while for her to answer. I’m not who she thought I was. That happens when your hair goes white and strangers start calling you sir. She has a lot to sort out. “No. He thinks I’m coming to visit, that I’ve gotten a ride. I’m sorry.”

“Don’t be. You are coming to visit, you have gotten a ride. I wouldn’t have missed it for the world. The abyss is about ninety minutes from Jack’s place according to the GPS. I can go on my own. Maybe I’ll stop off to see where D. H. Lawrence is buried. That was the last place Mom and Dad visited, apparently, before they took the plunge.”

“Stan, don’t—”

I hold up my hand. “Or I’ll wait for you in town, if you like, in case it doesn’t go well with Jack. We can talk about me later. You should probably think about what you’re going to say to Jack.”

But she has one more revelation.

“Simon Deetermeyer’s my dad,” she says. “That’s how come I know so much about ACABs. I’m not really an alien. I’m knocked up and thirty-three and desperate. I’m sorry.”

“That’s okay.”

“He was so excited when you came in. It’d been a while since anyone had found him.”

“How’s your dad doing? He hasn’t been answering my emails.”

“His funding was cut. He’s taken it pretty hard. Nobody knows where he is. The house foreclosed. That’s why I have to move out. It was only supposed to be temporary anyway. I’m not worried. I’ll figure it out. He’s done this before, totally lost it. Dad’s crazy.”

“I sort of figured that. Lots of brilliant men are crazy.”

“You sure you’re okay?”

“I’ve never been better.”

She accepts that. It must show. “This’ll be good,” she says, “knowing you’re waiting. It’ll force me to get to the point.” She gives me directions to Jack’s place like it’s no big deal. She’s just going to see a guy about her life.

Jack’s place is one of several lavish homes carved into the foothills near Taos for rich musicians, artists, and the like. I’m sure there’s a celebrity chef or two on these winding roads. I let her off at the gate with Avatar and a backpack, and Jack buzzes her in.

“Hey,” I say. “If it doesn’t work out. I have plenty of room.”

“You’re too nice,” she says.

“My dad told me there was no such thing, but he was an alien.” I wonder how he’d have felt about it if he’d lived to be my age. I imagine him feeling pretty much the same.

As we watch Katyana and Avatar walk up the drive, Myrna whimpers with regret, but I tell her not to worry. Katyana said it herself, Jack is no alien.

I wind around the hill and park on a curve off the road with a nice view of the night sky. Myrna sits in the front passenger seat, still warm from Katyana, and wonders what’s up. I turn on my phone so Katyana can call me whenever she gets the chance. I’ve left it off as we’ve crossed the country, enjoying the silence. It’s stuffed with messages I ignore.

I told Katyana I would wait in town, but what’s in town? Just more trouble for my credit card. This place is a lot different from last time I was here thirty years ago when there were adobe huts where Jack’s house sits. I wait under a myriad of stars. The more I look, the more there are.

My phone lights up. It’s Ollie.

“Thank God,” he says. “You’re alive. I’ve been calling and calling. Don’t you ever check your fucking messages?”

“My phone was dead,” I lie calmly. “What time is it there? Must be late.”

“Where are you?”

“I’m almost there. It’s just up the road, but I plan to wait until sunrise. No sense trying to find an abyss in the dark. You should see this place, Ollie. The stars are fucking unbelievable, just like Mom always said. It’s an incredibly beautiful mystery.”

“She said that sort of thing to you, Stan.”

“She said it to you too, Ollie. You just weren’t listening.”

“Mom was crazy, Stan.”

“We’re all crazy. Pick your crazy.”

“So you still with this young girl?”

“That’s up in the air at the moment. She more than likely will need a place to live. I’m waiting to see.”

“You’ve got to be joking.”

“I have plenty of room. She’s broke and pregnant. She wants to keep the kid. She hasn’t said so, but it seems likely.”

“Jeez, this is your kid?”

“Right, Ollie. It’s my kid. Somehow the vasectomy and being gutted like a fish didn’t do the trick.”

“I’m sorry. I was forgetting.”

Fucking incredible. I laugh out loud, electrons dancing in the midst of the Milky Way, inconclusive evidence of intelligent life. Another call comes in. It’s Katyana.

“I have to take this,” I say.

“Listen to me, Stan.”

“Later, Ollie.”

I answer.

“Come get me,” she whispers. “I’ll be by the gate.”

I don’t have to ask how it went. I wind back around the hill to where I left her. Avatar sits beside her like a good soldier. They get in and settle into place. I let her have a moment. Myrna showers Avatar with kisses.

“Abyss or home?” I ask.

Make no mistake. The abyss is real. It’s a new life either way.

“Home,” she says, and smiles at me, almost like she’s happy. Shelter from the storm. Maybe that’s why the aliens came in the first place. It was all an accident. There was no mission. They found themselves here far from the turquoise skies of home and had to make the best of it.

This time we drive straight through, swinging by her garage apartment to pick up a few things. We want to make it home by Christmas, and we make it just in time to watch It’s a Wonderful Life and cry, the both of us. I set my phone up on the TV and we pose for a photo, the four of us, teary-eyed, smiling, and wagging, and send it to Ollie with our Christmas greetings to let him know we’re okay, to maybe cheer him up a little. He’s alone these days. Nobody wants to be alone on Christmas. We’re holding Katyana’s Paint by Number between us, lifted from her dad’s collection of alien artifacts, as a reminder of where we came from.

The baby—she does want to keep it—is due around Independence Day. Make of that what you will. No fireworks, however. They scare the shit out of Myrna. Next week is the New Year and fifth Tuesday, a serendipitous synchronicity we plan to celebrate in the ACAB way.

See you down by the riverside.

“Adult Children of Alien Beings” copyright © 2015 by Dennis Danvers

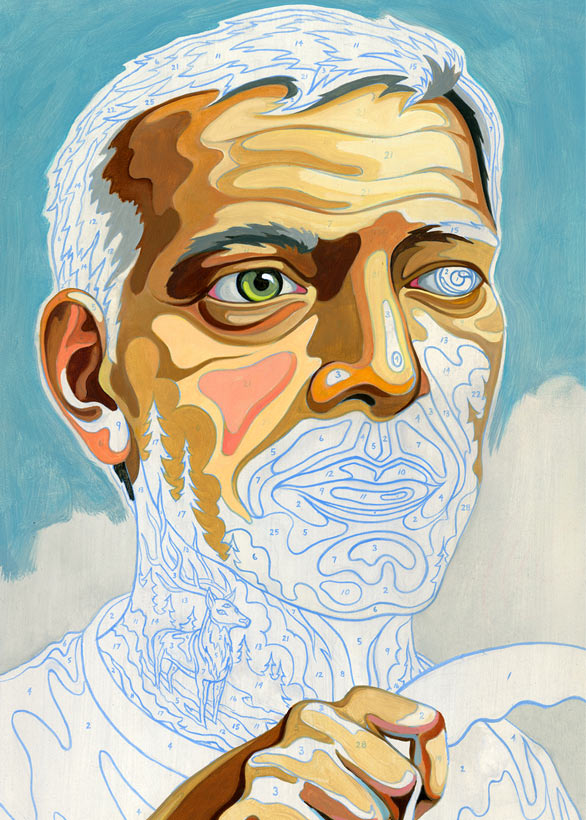

Art copyright © 2015 by Chris Buzelli

You know that I am now obliged to search for oddly-colored paint-by-numbers as evidence? Right? Right!

As I was reading about the ACAB website and the image of the paint by numbers scene, it was really difficult for me to not immediately google it in a new tab! Also excellent, excellent illustration.

You are aware that ACAB stands for All Cops Are Bastards, right? The wariness of authority is in the background.

Nicely ambiguous, well done.

To my nose there’s a whiff of Clifford D. Simak about it, like the spices mentioned. Warm, confident and comfortable, and they even walk dogs.

Fyi, there’s a follow-up, which will be up May 24th.

I read ‘Orphan Pirates of the Spanish Main’ first, so I know I accidentally read them backwards. There was a lot of the same here and in ‘Orphan Pirates,’ but I actually think I like this first piece better. The scene in the grocery store had me laughing out loud! I love these stories about Stan and his alien parents, they are so honest and real and enjoyable. And the writing is just plain old fun. Looking forward to reading more work by Mr. Danvers!